Nike Strikes Back At Me in the New York Times

A big, flawed New York Times article on A’ja Wilson and Caitlin Clark

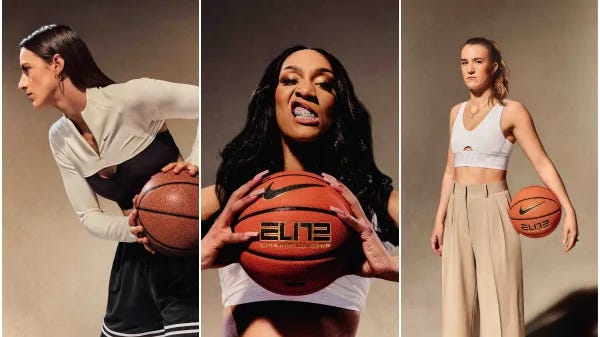

Nike, via a front page New York Times article, pushed back on…me. That’s my personal narcissistic takeaway reaction because the story is really about A’ja Wilson as signature sneaker venture. A lot was invested into the piece, written by former Lakers beat writer Tania Ganguli. There are scenes on location in Paris, where Wilson is visiting as a Nike representative for men’s fashion week. There’s a large, professionally done NYT photo of the article’s subject, dressed in splendid attire. The title suggests a lot.

The Best Player in the W.N.B.A. Now Has Her Own Shoe. It Took a Long Time

The subhead suggests even more.

The marketability of A’ja Wilson offers a case study in race, fame and gender.

Oh the part that mentions me? Right here:

A prominent Substack sports columnist, Ethan Strauss, suggested that Nike was delaying Ms. Clark’s shoe because of Ms. Wilson’s coming product, calling it “corporate malpractice” to not cash in on Ms. Clark’s popularity.

Yes, I said this. Corporate malpractice from a company caught up in bizarre social justice games. Someone asked me why I care if Nike makes money off Clark. I’m not a shareholder. I didn’t receive some emotional boost from the corporation’s stock bumping up after a trade deal with China was announced.

I think I’m mostly just fascinated by a common denial over the connection between ideology and tangible negative consequences. Many in my milieu will roll their eyes over cringe social justice content. It looks so silly now, in 2025. But there’s a mental block on believing that a corporation would burn billions over now unfashionable manners. Among high functioning friends, there’s this assumption of a guardrail between “silly college kid ideas” and “real results.” At some point, an adult in the room stands up and stops the madness. Nothing gets out of hand. Nothing that should function ceases to function because of race and gender obsession among the college educated.

Ideas have consequences though. They inform actions and agendas. If enough people in your company believe that it’s prima facie unfair that X celebrity endorser is getting attention, they’ll focus more on the unfairness than on benefitting from the attention. I really do think this has happened at Nike with Caitlin Clark. I’ve heard from enough sources and seen enough of their external messaging. Nike will promote her with commercials and product soon enough, but the years long delay is related to what they perceive as a cultural minefield.

Signature shoe topic aside, since she entered the WNBA, the only solo Caitlin Clark ad Nike has produced is a 15 second social media-targeted spot of the Fever guard shooting in front of a barn. It was part of a “Just Win” campaign that featured a bunch of other Nike athletes.

Tanya Hvizdak, Nike’s vice president of global sports marketing, said Nike was not delaying Ms. Clark’s shoe for Ms. Wilson. She said creating a signature shoe took time and disagreed with the characterization that it had taken too long for Ms. Wilson to be awarded a shoe.

When Nike wanted to promote Diana Taurasi in 2005, they made a shoe for the UCONN star’s inaugural WNBA season. Putting out a sneaker is an investment, but you’d expect, say, a shoe company, to pull off such a Herculean task.

It’s with some chagrin that I’ll give the rest of this A’ja Wilson feature a soft Fire Joe Morgan treatment. I’ve got personal misgivings in doing so because I’ve met Tania Ganguli, have nothing against her, and believe that most of my issues with the piece are downstream of what the article’s principals suggest. Here goes.

A’ja Wilson, a center for the Las Vegas Aces, is widely acknowledged as the best player in the Women’s National Basketball Association. She is something like the league’s on-court answer to LeBron James or Michael Jordan.

More like Tim Duncan.

If Ms. Wilson were playing in the National Basketball Association, she would have long ago gotten a signature shoe, the on-court footwear designed with and for a player.

Getting a shoe isn’t a pure meritocratic reflection of on court value. Notable elite NBA bigs either never got their own sneaker, or if they did, saw very few people buy that sneaker. Dirk Nowitzki never had a signature shoe. Anthony Davis has no signature shoe. Nikola Jokic left Nike to get a shoe with a company called 361°. Wilson is a big who hits a lot of post up shots. There’s no real NBA track record of such a player ever selling shoes at scale.

For years, marketers largely ignored the women’s game. But Ms. Wilson’s star has risen alongside that of the league she plays in, and in early 2023, Nike finally told her that it planned to create a signature shoe for her.

“I probably cried for a couple of days,” she said.

This part of the article is normal. It’s about to get weird, though.

The plan remained secret, and her fans got angry as Ms. Wilson continued to dominate on the court — winning another championship in 2023 — without any news of a shoe. Fans were happy last May, however, when Nike announced that it would release her signature shoe, the A’One, this month, alongside an apparel collection.

Wait what? The plan remained secret? For over a year? This isn’t generally how the industry works.

When the shoe was announced, Nike leaned into the controversy: Ms. Wilson wore a sweatshirt that had “Of Course I Have A Shoe Dot Com” written on it.

This whole “controversy” is such a corporate ouroboros and perhaps hard to track for any non extremely online person.

The A’One went on sale on Tuesday, with a “Pink Aura” version, making Ms. Wilson the first Black W.N.B.A. player to have a signature shoe since 2011.

Candace Parker had signature Adidas shoes until 2022, but fair enough.

Last season, interest in the league spiked, buoyed by the popularity of the rookies Caitlin Clark and Angel Reese. Brands rushed to play catch-up.

I don’t think Angel Reese is selling out road arenas.

The 2024 championship game drew 18.9 million viewers, beating the men’s championship game by about four million, according to Nielsen. That interest has trickled up into the W.N.B.A. as the players moved there, too.

The players, eh?

The sports media kabuki of pretending like Caitlin Clark is simply one of many, as opposed to one of one, remains absurd. We all know that she caused a boom in women’s basketball reminiscent of Tiger Woods’ entrance into golf, but there’s so much WNBA resentment over this reality that Nike and the New York Times will play defense against what everyone knows. Indeed, Nike’s corporate malpractice is connected to this neurotic pretense. For over a year, they’ve featured Clark in “roster ads” where she’s one of a few WNBA players.

Women’s models make up a small portion of the basketball shoe business, said Matt Powell, a retail analyst with BCE Consulting, in part because many female basketball players prefer wearing a men’s shoe.

Caitlin Clark is a great example of this phenomenon. She’s obsessed with Kobe Bryant and wears his shoes. One flaw in Nike’s girlboss-forward advertising obsession is that many female athletes admire male athletes. People often look outside their own identity groups for inspiration.

Mr. Powell, the industry analyst, also said he believed that Ms. Wilson’s shoe would do well among women’s basketball shoes, in part because of the heightened interest in the W.N.B.A. and in part because of its relatively low price. Adult sizes are $110 and children’s $90, compared with $190 for Mr. James’s signature shoes or $130 for the Sabrina 2.

“Do well among women’s basketball shoes,” isn’t exactly a ringing endorsement. But hey, there’s clearly tremendous demand for this product that Nike is making super cheap for some reason.

In April 2024, when news broke that Nike was planning a signature shoe for Ms. Clark, then heading into her rookie season with the Indiana Fever, it set off a firestorm. The news of Ms. Wilson’s shoe wasn’t public yet. Her fans wondered if racism played a part in giving Ms. Clark, who is white, a shoe before the much more professionally accomplished Ms. Wilson, especially since the only other active players with signature shoes — Ms. Ionescu and Breanna Stewart, a two-time M.V.P. — are both white.

Looking back, it’s extremely funny that Nike allowed itself to bear the brunt of these racism accusations for three weeks and we’ve still no explanation as to why. The accusations are insane, but so too is not simply admitting that A’ja Wilson has a shoe. Perhaps this was all a marketing ploy by Nike to make themselves look “bad” for racistly ignoring Wilson only to later go, “Surprise!”?

“It was very hard for me to navigate, only because in the back of my mind I’m like, ‘Yes, I know a shoe’s coming, but I really have nothing to share,’” Ms. Wilson said. “And to constantly be in those conversations and constantly having my name dragged through the mud and having my résumé dragged through the mud is really hard.”

So Wilson went through psychological turmoil all to keep a shoe deal secret for reasons nobody articulates. Again. Why did this happen?

Others noted Ms. Clark’s exceptional popularity: She was selling out arenas and causing opponents to move their games to bigger venues. Games she played in set viewership records.

I identify as “Others.”

Strangers debated Ms. Wilson’s merits. Some said that her personality wasn’t charming enough, or that her style of play lacked charisma. Frontcourt players are sometimes thought to be less marketable because their style of play is often less flashy.

As mentioned previously, front court players aren’t “sometimes thought to be less marketable.” When it comes to shoe sales, they simply have always been less marketable. This quirky reality confounds the article’s foregrounding of race and gender. Basketball bigs are victims, in a way, of heightism. Most times, it’s short people who can credibly claim to be victims of heightism. In this case, the tall basketball players are dismissed or resented for their advantages while their shorter peers become more popular. I’ve heard NBA centers complain about this, but I doubt they’re forming an interest group over their highly niche plight

Ms. Wilson has not shied away from discussing the impact of race on why she is sometimes called not marketable.“ It’s 100 percent about race,” she said. “And it’s one of those things where we can sit there and say that all the time, but there’s going to always be someone that’s like, ‘Well, no you’re just making it about race.’”

I don’t know how to negotiate with Wilson’s perspective here. It’s tough to meet someone part way when they’re opening with “100 percent.”

I was prepared to concede that “White Iowa girl” is part of Caitlin Clark’s branding and it’s hypothetically plausible that a Black version of Clark would get less attention. But A’ja Wilson isn’t a Black version of Caitlin Clark. Again, she’s more like a female version of Tim Duncan.

The pertinent reality for Nike and women’s basketball more generally is that there actually isn’t a Black version of Caitlin Clark. At least not yet. Only Caitlin showed up for the job of being Caitlin. Only Clark is an industry unto herself. You get that. I get that. The world’s biggest sports apparel company? The New York Times? They’re still too worried about the goose being White to fully admit that she alone is golden.

Brief note not related to overall piece: Kill your darlings and all that with your own writing but gotta say..."They’re still too worried about the goose being White to fully admit that she alone is golden," is a great line.

There's a not that unlikely world where Clark gets injured or America just gets bored with the WNBA after a passing fancy with a unique three-point shooter. If that happens, the whole league and Nike will have missed out on millions and millions and millions of dollars. There is no guarantee the Clark window last forever and they delay monetizing it at their peril.