The Diversity Man

Richard Lapchick is the Robin DiAngelo of sports, with a backstory that reminds of Jussie Smollett

One great unresolved tension of this era is that our institutions never quite sort out how much of the diversity focus is a business plan versus a moral cause that transcends mere business. The implication is often that it’s “both,” but you’re never instructed as to which aspect should predominate and whether one ever comes at the expense of the other.

When faced with these complicated questions, all the major sports leagues look to one man for easy answers. Specifically, they seek this guy’s race and gender report card, a public checkup now adhered to by the NFL, NBA, and NHL. The announcement of these report cards makes the news, bringing shame or celebration to these institutions based on an assessment of how non-White and/or male they are.

The sports leagues do all this because they are seeking new customers, much as they might try to cloak the endeavor as something grander. The report cards serve as a way to stoke change, hopefully profitable change. Those in charge can’t help but see moral progress as a marketing strategy, and in Central Florida, they find someone who sees the world exactly as they do.

He is celebrated as a saint by mainstream publications like ESPN.com and Sports Business Journal, both of which he writes for. His local paper covers him with an almost-childlike awe.

His message is mostly a heroic biography, by his own repeated telling. The tale is literally unbelievable, but no matter. It’s a good story. Whether it’s true is besides the point. It’s part of a “truth to power” shtick that so appeals to the powerful.

“Diversity is a business,” says “racial conscience of sport”

Meet Richard E. Lapchick, a boomer White man. Normally I wouldn’t dwell on a person’s census category details, but that’s literally Lapchick’s focus. He is an Eminent Scholar and Endowed Chair at University of Central Florida’s College of Business. His own biography at UCF describes him as “the racial conscience of sport.” The aforementioned race and gender report cards come out of the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport (TIDES), a fiefdom under his aegis.

If you’re wondering how “College of Business” can be reconciled with “racial conscience of sport,” the answer is simply that Lapchick and his customers tend to view their moral aims and business aims as one and the same. Indeed, I reached out to Lapchick to ask about this, and was fairly stunned by the corporate candor on this subject. He said:

I think when we started out it was more of a moral consideration, but it's clearly now a business. Diversity is a business, it's as simple as that. And the leagues know that they're trying to build a larger fanbase in communities of color and it's a business. I think the morality of it plays into it, but I think the business decision is what drives it now.

So if diversity is a business, then how does Lapchick’s function?

I think the commissioner's offices in particular see the racial and gender report cards as a kind of bully pulpit because the league offices do pretty well if you had a chance to look at the report cards, but it's at the team level where a lot of it pulls down. So they use the racial and gender report card to talk to the teams about, "We're getting this lower grade because your data isn't where we need it to be to have a diverse workforce."

So, by the Lapchick explanation, the report card allows commissioners to cite a third party’s imprimatur when arguing for what the commissioners all want: more diversity in the team ranks. As Lapchick said in another interview, “The leagues are doing pretty well, but it’s at the team level where the lags really take place, at the local level.”

League offices are often at a distinct remove from ground-level professional sports, where decisions can lead to tangible wins or losses. It is easy for a commissioner to proclaim, from his Midtown skyscraper, that you should hire more of X or Y type of person as your coach or general manager, but harder to fulfill such wishes when a small difference between candidates might be the margin between “playoffs” vs. “disappointing season, superstar leaves, team spirals toward a decade of irrelevance.”

From the commish perspective, more diversity in hiring is a bulwark against possible discrimination lawsuits, plus a potential pipeline to untapped fan markets. It’s also just what a nervous executive does in a time of social upheaval. Lapchick:

During the racial reckoning, several organizations came to us and — we weren't doing racial report cards on — asked us to do private report cards, including NASCAR, the West Coast Conference, we're talking to the Pac-12. We've had a number of discussions with other leagues, the National and Soccer League, US Olympic and Paralympic committee. We've all done report cards on a fee basis as consultants.

Lapchick is not shy about what the 2020 racial reckoning accomplished for his business. On the aftermath of George Floyd, Lapchick told the Sports Business Journal:

I realized after the murder of George Floyd and the racial reckoning that I want to devote 100% of my time for the rest of my working days to anti-racist activities. Since the murder, I have been inundated with 85 speaking requests, 10 new racial and gender report cards, and numerous instances of asking me for advice on racial and gender issues by athletic departments and pro teams.

While I cannot tell you what a Lapchick consultancy fee might run an organization, I can tell you that his speaking fee is listed at between a hefty $10,000 and $20,000. For more specificity on the pricing, I called his agency, which explained:

His standard fee for a 45-minute to one-hour presentation would be $15,000, and then that would be in addition to first class airfare, ground transportation, and hotel.

Nice work if you can get it.

In 2021, Lapchick announced that he was stepping down from his position as director of the DeVos Sport Business Management Graduate Program and signing with The Harry Walker Agency, which represents the public speaking affairs of Barack Obama, Michelle Obama, Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, Oprah Winfrey and Tom Brady.

If diversity is a business, as Lapchick puts it, then his business is booming. He appears to have become something of a Robin DiAngelo figure, a professional White ally, well-positioned to profit off professionals looking to become White allies.

But how did this White boomer, working out of Orlando, become the lavishly paid racial conscience of sport? Why didn’t this particular role in society fall to a Black person or a woman? It starts with a story that, in its awfulness, is too good to be true.

An Attack Disputed

Richard Lapchick is the son of legendary basketball player and coach Joe Lapchick, a 1966 Hall of Fame inductee. Beyond his on-the-court accomplishments, Joe Lapchick is credited as a force in bringing racial integration to the NBA. Richard has retold his early memories of those days in multiple publications. From USA Today:

My earliest memory of the backlash as a child was looking outside my bedroom window in Yonkers, New York, where I was raised. I was five years old. I saw my father's image swinging from a tree with people under the tree picketing. For several years I would pick up the extension phone in the house. My dad did not know I was listening to hear angry people shouting racial epithets at my father.

The son embarked on a journey to emulate his father’s social justice accomplishments. According to Lapchick and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, young Richard was knocked out because he defended then-Lew Alcindor against racist bullying. By the ‘70s, he was organizing anti-apartheid protests while working as an assistant professor of political science at Virginia Wesleyan College. In 1978, while engaged in an effort to protest South Africa’s inclusion in the Davis Cup tennis tournament, then being held at Vanderbilt University, Lapchick’s life changed. He was, by his own account, assaulted in an attack so cartoonishly vile that it would make international news and vault its victim to fame. Lapchick:

I was working late in my office in the school library. There was a knock on the door at 10:45 in the night. I didn’t hesitate opening the door since school security would often check on me while doing their rounds. Instead of the campus police, it was two men wearing stocking masks who proceeded to cause me [harm]

In Lapchick’s retelling, the men, who somehow knew to find him in the library office after most everyone else on campus had left for the night, threatened the associate professor over his Davis Cup activism:

“They knocked me across the room, and I landed on a steel sculpture, which is made out of spikes, so I punctured my left shoulder,” he said. “They picked me up and put me in a chair, tied my hands and feet, stuck a glove in my mouth and tied that, too.

“One of them said, ‘Are you going to continue what you're doing?’”

From the New York Times, on Lapchick’s version of events:

He said that he was beaten unconscious with a file cabinet drawer, and that when he awoke his attackers were carving on his stomach.

That carving? The word N-I-G-E-R, etched with a pair of scissors.

In the aftermath, martyred Lapchick made the connection to his father rather explicit.

I knew that night that if people go to the lengths that they did to stop my dad 28 years before, they would try to stop me at this point.

It was quite a story and it inspired a lot of sympathetic passion. From a Washington Post article titled “Celebrities Back Injured Va. Activist”:

More than 100 nationally prominent people, including former U.S. attorney general Ramsey Clark, singer Harry Belafonte, author Kurt Vonnegut, NAACP executive director Benjamin Hooks and comedian and activist Dick Gregory, have formed a New York-based Committee for Justice for Richard Lapchick.

Just like that, the young professor had gone from relatively anonymous “Va. Activist” to someone on the minds of Kurt Vonnegut and Harry Belafonte. From there, Lapchick was off and running as a public figure, eventually attending Nelson Mandela’s inauguration as a personal guest of the president. Some would call such support earned, given what Lapchick purportedly suffered.

The problem with the story Lapchick’s retailed for years is that back in 1978, the authorities commissioned with investigating this incident didn’t believe it to be true. Their doubts were not hidden, and were well-represented in the local media at the time, even if the current media has totally lost track of this aspect when repeating Lapchick’s version.

Dr. Faruk B. Presswalla, the chief medical examiner for the Tidewater area, openly argued against Lipchack’s version of events. Presswalla specifically questioned the carving of N-I-G-E-R in a WaPo article titled “Activist's Claim of Injury From Beating Disputed”:

He said he believes the carved word "niger" was a self-inflicted wound because of the manner in which it was written. "It's written with squared letters of equal size and equal distance apart in horizontal straight lines with each letter having multiple strokes." He said the "i" was dotted.

The medical examiner said the multiple strokes, called "hesitation marks," are normally found on self-inflicted wounds. "It's not the type of thing that a person assaulting another person would do." He said such a wound from an assault would be scratched and would not contain square letters nor traces "one on another."

Presswalla wasn’t finished:

He also said a hernia that Lapchick claimed was a result of the beating was an injury that the college professor had before the attack. "It was an antecedent. It was not related to the assault," Presswalla said.

Presswalla’s assessment kicked off a round of skeptical Lapchick coverage in the local press. Ironically, I’d be mostly unaware of such coverage if not for Lapchick’s own Broken Promises: Racism in American Sports, a 1984 work that, for about half its pages, dwelt on the incident and its aftermath. If not for that book, I’d be ignorant of the degree to which police disbelieved Lapchick, and I’d be clueless as to how he made strong skeptics of the local media.

Overall, Lapchick’s impassioned defense against these doubters has the opposite of its intended effect. He may be fortunate that so few people read it. The book would be almost completely lost to obscurity but for a Sports Illustrated review that panned it, declaring, “Lapchick simply isn't a good writer and Broken Promises suffers greatly because of it.”

In 2020, Lapchick himself referenced that scathing review as his inspiration for doing racial and gender report cards.

The Sports Illustrated reviewer was very critical about this kernel of information about hiring practices in professional sport. And his perspective is, why is this guy bringing up things of the past? Sports are completely integrated. He of course was talking about the playing fields, which were mostly integrated by that time in 1984. But I was so angry that he took that point of view about that particular part of the book that I decided to do these racial and gender report cards on a regular basis, and we started in 1988.

Cool story, but the review doesn’t include a section like Lapchick describes. Ironies abound here because, beyond skewering him for being a self-aggrandizing White savior (“There isn't a single mention of the men and women in sports—athletes, coaches, officials—working toward improving race relations, unless they are black or named Lapchick.”), the Sports Illustrated review actually attacks Lapchick for his inaccuracies. Specifically, the reviewer noted Lapchick’s errors in retelling the case of when basketball player Quintin Dailey was accused of sexual assault by a nursing student. Beyond the errors noted, the reviewer appears not to have been wild about Lapchick’s framing of the situation, which included this passage:

Even if he was guilty, why was he singled out for such an unrelenting torrent of criticism? Other athletes have been charged with similar or worse sexual offenses and have paid much smaller prices. I honestly do not know the answer, but I keep coming back to the same question: Would the reaction have been the same if the woman had been black?

The beauty of unskilled rhetoric is that it can’t hide much. For instance, the book reveals that, in his initial interviews with media, Lapchick opted for “deleting” certain details of the attack and misled reporters into believing that the full racial slur was etched on his chest. I wouldn’t have known that Lapchick lied to reporters but once again, there’s the book, helpfully giving readers reasons to be suspicious of the narrator.

Lapchick’s retroactive explanation for why initial interviews don’t match his current story is that the authorities told him to obscure aspects for the sake of the investigation. Maybe so, but one takeaway could be that our Man of Conscience is willing to lie for expediency.

And this is how the book goes. So many details willingly offered make the story seem implausible. Lapchick tells us that his attackers, though lashing out on behalf of South African tennis, had American accents.

He then tries to tie that loose end, saying, “Of course, I later realized that if South Africa was behind the attack, the last thing they would do was send nationals with South African accents.”

How do we know that South Africa is implicated here? Well, according to Lapchick:

The first man then said, “You know you have no business in South Africa.” The confusion about why they were there was over.

So the reader is left with the classic, simple story of an associate professor at a small college, in his office at 10:45 p.m. after other workers go home, brutally accosted in defense of South African tennis by two American-sounding men, who somehow know to look on campus, late at night. The attackers are obsessed with the small-time prof’s activism and simply must intimidate him out of his plan to thwart a competition happening over 700 miles away. Despite being brutes who idiotically etch the name of a landlocked African nation into the academic’s abdomen, these wildly violent racists manage to evade any detection. The oafs also cut their victim haltingly, as though they’re feeling pain with every slice.

Quoting a detective in the Nashville Banner:

The whole thing just did not ring completely true.

Quoting chief medical examiner Presswalla, in the New York Post:

I’m sure this is going to be ammo for the conservative red-neck types to say liberals are pinkos and liars—which includes me because I’m a liberal.

By the way, both quotes can be found in Lapchick’s book, which is replete with passages that seem to destroy the author’s story. We will never definitively know what happened on campus in 1978, but it’s difficult to read Lapchick and not be reminded of another famous tale involving two masked racist men, attacking a relatively obscure public figure with bizarre tortures, all because they supposedly fear his anti-racist activism.

In the case of Jussie Smollett, his self-aggrandizement was conveyed when he bragged, “I’m the gay Tupac.” Lapchick may have been even more ambitious with his comparisons. In a statement meant for media at the time, he said, of the police disbelieving him:

More than a few people have suggested to me that the TV broadcast of the life of Dr. King last week may have created a climate for the violence that I was a victim of last Tuesday. I wonder if it also created the climate for the police to attempt to discredit me as they had done to Dr. King prior to and after his assassination.

Somehow, someway, Lapchick survived Dr. King’s fate.

It’s apparently been forgotten by all media outlets that reference his bio, but Lapchick’s disputed story was national news at the time. It was a colorful controversy, one that included a battle over whether he submit to a polygraph. These aspects have been pushed aside, however, in exchange for Lapchick’s preferred version, which now grows new details. Take this scene that seems straight out of a pre Twitter Oscar-bait movie and has been repeated a few times to modern interviewers, but curiously wasn’t mentioned at all in the 1984 book. From Mike Bianchi’s Orlando Sentinel column on Lapchick in 2021:

As Lapchick lay in his hospital bed at about 4 o’clock in morning with liver and kidney damage, he heard three women talking in the hallway. And one by one, three Black nurses came into the room and kissed his hand.

“I didn’t know white people cared,” one of nurses said.

When Lapchick heard those words, he became more determined and emboldened than ever.

True or fake, this schmaltzy retelling captures why Richard Lapchick has been so successful. This is a wish of many White liberals, fulfilled, the savior complex fully realized.

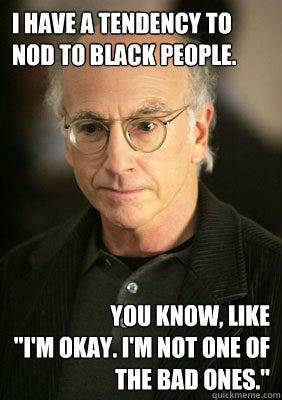

It also helps explain the irony of how a White boomer has managed to reap more rewards from Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in sports than perhaps anyone else. Think of who Lapchick’s customers are, for the most part: White commissioners and business leaders. These people like Lapchick because they are Lapchick, or at least want to be. He’s a White guy getting positive media coverage on issues of race. Who better to show them how to be “not one of the bad ones”?

Here, I reference former ESPN president John Skipper, an energetic liberal White boomer whom Lapchick cites as a confidante:

The best display of the Skipper Doctrine happened in February 2016 at Re/code’s media conference. Skipper announced, “There is not enough Black media in this country. There is not enough Black-owned media in this country. There are not enough sites run by people of color.” That presentation of a problem swiftly turned into a brag. Skipper wanted the room to know that ESPN had 74 of the nation’s 85 national sports writers who were women or people of color. He closed with a condemnation: “Shame on the rest of the press media.”

Hooray for us, the good ones. Shame on you, the bad ones.

Men of a certain generation grew up on optimistic idealism, thinking the game of high-minded ethics would be won. Racial justice could be achieved, if only we might imagine harder.

My generation and the younger generations beneath might be more obsessed with “diversity,” but almost nobody within them seriously envisions a reconciled future. The olds take to this all like they’ve finally found the antidote. The young depressively say, “Do better,” and the boomer leaders happily exclaim, “We’re gonna do better!”

NHL commish Gary Bettman practically beams with pride as he describes his sport’s diversity initiatives — initiatives that include a shiny new report card from Lapchick. At the very moment the sports media is crushing hockey over its DEI issues, Bettman seems enraptured by the idea that this whole puzzle can finally be solved.

Of course, it’s never so easy and Lapchick is an example. One of his contributions to sport is pressuring NFL franchises to adopt the Rooney Rule, which dictates that all teams must interview at least one minority candidate for head coaching positions. The rule has largely failed in its aims, while setting off awkward bits of game theory. Two decades later, the league’s head coaching ranks are about as White as they were in 2003.

The Rooney Rule succeeds as an illustration of boomer naiveté, though. The rule’s premise is that these old White owners just need exposure to Black candidates and then their racism will disintegrate upon impact. Of course, modern life is more complicated and interconnected than this theory would suggest. The in-person interview process, in this time of constant communication, isn’t exactly how coaches are recruited. DeMeco Ryans just got hired to coach the Texans because he was an enormously successful defensive coordinator with the Niners, and he’d been a hot HC prospect for months. It didn’t happen because Janice McNair was forced to meet with Ryans, who played six seasons for her Texans, and she thought, “Wow! This Black guy’s alright!”

On the other hand, funneling a bunch of doomed candidates into a sham interview process, all because of their race, has some negative externalities. Beyond the humiliation involved, you’re training organizations to tokenize candidates rather than to take them seriously. Curiously, the NBA, which has no Rooney Rule, has a lot of Black coaches, versus the NFL, which has a Rooney Rule but very few Black coaches. Presented with the Rooney Rule aftermath, Lapchick insists that it’s not the rule’s fault.

The league has strengthened the Rooney Rule over the years, but it doesn’t seem to be getting any better. The light should come on for everybody that this isn’t about the Rooney Rule, it’s about who the owners are.

It’s not my rule that failed the league; it’s the league that failed my rule.

It’s a simplistic view, one that reduces outcomes to the good vs. evil perspective of an ideologue. There’s no accounting for whether Lapchick’s solution actually impeded an institutional ability to see candidates for who they are, versus seeing them as tokenized means to easy ends. There’s no reckoning with whether there’s a downside to hamfisted bureaucratic efforts towards hiring people just because they don’t share Richard Lapchick’s census categories.

Speaking of, that’s the other aspect that likely resonates with Lapchick’s fellow White Boomers. There’s the promise of guilt expiation, minus personal cost. None of these league executives are keen on giving up their job for the diversity cause, any more than Lapchick wishes to give up his speaking fees, or move from either of his residences in towns that are, respectively, 88.7% and 91.5% White. No, the boomer way is progress through energetic idealism, but not so much through self-denial. If there’s pain involved in this process, it will be someone else’s to bear. To quote Lord Farquaad: “Some of you may die, but it's a sacrifice I am willing to make.”

Meanwhile, the racial conscience of sport isn’t just living, but thriving, to the tune of five figures per speech, as the White man commissioned to tell leagues that they should hire fewer men like himself.

Predictably, I did not get word back from Lapchick when I reached out to discuss the hoax accusations. Thankfully, the first interview I did with him at least yielded some good moments.

At one point in it, he said:

When you have a job opening, you get the best people in the room and then hire the best person. And to me, having a mandatory diverse pool of candidates is something that I feel makes things change. I think without that, things are unlikely to change.

He then paused, and pathologized:

I'm guessing you're White. White men don't give up power as easily as historically, they certainly haven't. But when it's mandated that they do, then things are possible to change.

If he’s correct in his theory, then who would know better? Indeed, it’s hard for a White man to give up power, especially when he’s getting paid $15,000 a pop to say that White men should give up power.

The only answer is to bring in Diversity Partners International. Its visionary CEO Kmele Foster should be able to diagnose and fix all the league’s diversity issues.

Brilliant. One of your best