Adam Schefter and the Problem of On-ness

ESPN and the cost of staying in front of the moment

Credit to Ben Strauss (no relation) from the Washington Post for this profile on ESPN’s NFL newsbreaker extraordinaire, Adam Schefter. If you’re into sports industry dynamics, it explains a lot. If you’re into an admirably dispassionate individual study of success, it has that too. One upshot is that, while you might want Schefter’s fame and might envy his money, you probably wouldn’t want his life. There’s a darkness in this reveal that reaching the mountaintop just feels like being buried.

I’m a big believer in this idea that the more specific a story is, the broader its themes are. So, I happen to think that this Schefter profile is illuminating beyond the guy. In the story of his extreme commitment I see the grinding prerogatives that millions live with. And, while aspects of Schefter’s rise are particular to sports media, his refusal to ever leave the digital workplace is something you’ll witness in a lot of professions. We’ve moved from working hard to lurking hard. I don’t think it’s been a good development, overall.

Working vs. Lurking

The Schefter profile gave me a lot to think about in regards to work, especially since I read it on the tail end of Las Vegas Summer League, an industry event I mixed in with a brief quasi-vacation. I feel blessed to have this newsletter and the flexibility it affords. This past year has meant a lot more work, because running your own business just has to mean that. Somewhat paradoxically, though, working longer hours coincided with more family time and present-mindedness. How could this happen?

The easy answer is that I now control when I’m actually working. Before, at jobs I was — I’d stress to add — fortunate to have, I wasn’t in control of the clock. I was on the NBA’s schedule, which waits for no one.

But it’s not simply a matter of avoiding games games games. Those have always been part of the gig, and beat writers who worked in the mid-aughts wistfully recall how manageable the job was back then. The big savings was in avoiding the modern communication flood that keeps you in a state of unceasing vigilance. Outside an institution, there just hasn’t been the same Slack/Zoom/Text/Email/Twitter alarm system tugging at me. I should emphasize that The Athletic was better than any place I worked for in terms of clock control. They were the best at allowing someone to go at their own pace, so long as that person produced.

But still, even if I wasn’t working, I was usually lurking. Almost everyone is, in that sort of job, if they intend to keep it. It’s a low-grade, nagging sense that you should be doing something responsive to the present moment. There’s so much happening and so many people talking at you — weekday, weekend or otherwise. So you stay in the loop, because your responsibilities are more obvious when the information is flowing. Sure, you can jealously guard your time and claim traditional hours where you’re off the clock. I knew a manager like that at ESPN. He was a hard worker. And he was fired, in the end.

So many of us are trapped in jobs with painful costs that are perhaps too modern to clearly articulate. We are history’s winners in many ways, cosseted with luxuries that our forefathers could never fathom. On the other hand, many of us in professional-class life are haunted by our jobs in ways and for reasons that are novel, the byproduct of advances in communication tech over the last decade or so. It’s yet another realm where we’ve innovated faster than our capacity to handle our capabilities.

Maybe our grandfathers hated going into the office, but at least the office was a real place, physically separated from the others. The present office has tentacles that reach into every device you use, wherever you happen to be. I can say that, and yes it sounds bad, but the description still can read as whining, softness. As I write it and read it back to myself I’m thinking about how precious it would all sound to my great-grandfather, who was a farmer in Hungary.

The totality of how bad it gets wouldn’t make sense to the workers of yesteryear. No previous generation submitted itself to this constant state of on-ness, so while its downsides are deeply felt, they aren’t easy to convey to people outside the currently working generations. The job isn’t compartmentalized but its miseries are. The cumulative weight is internal, psychic and, of course, less worthy of reflexive sympathy than the plight of the coal miner who loads 16 tons. I’m not saying the professional-class life is necessarily worse; just that it can be a heavy state. And while the coal miner or great grandfather Arnold might scoff at the idea of laptop class plight, our well remunerated sports newsbreakers have a way of making modernity look like hell. For instance, this passage on elite NBA newsman Shams Charania, from my guy Ryan Glasspiegel:

Asked about his screen time, Charania answered that the typical amount is 17-18 hours per day—and that it climbs over 20 hours during frenetic periods of the NBA Draft and free agency. It makes his ‘heart sink’ when he is on a flight where the Wi-Fi doesn’t work. He mostly forgoes driving for ride-shares—his trips from the suburbs into Stadium’s offices adjoining the United Center are about 40 minutes each way, a couple times a week—lest he miss a scoop while behind the wheel.

Mr. Burns’ taunting sign read, “Don’t Forget: You’re Here Forever.” But a lifetime job seems almost quaint and comforting compared to the current condition of many different gigs that all seem to follow you everywhere. Don’t Forget: You’re Here Even When You’re Not.

The Great Reclamation

What I’ve described is a miserable state of affairs for many, but I’m happy that it’s fueled a righteous backlash, a reassertion of personal sovereignty if you will. The pandemic accelerated “The Great Resignation,” the trend of employees quitting their jobs at a shocking rate. That trend might be reversing as a recession threatens. People still need money.

The stickier employee-led outcome is the physical departure of workers from the office. Or, as Shark Tank panelist Kevin O’Leary succinctly put it: “They’re never coming back.”

I see this as a renegotiation of territory in response to a sustained incursion. History can go this way; it’s a little more complicated than one long onslaught of the strong dominating the weak. For years, corporations have been moving their digital junk into our homes, while demanding that we physically attend work in theirs. Eventually, they’d moved so many of the relevant tools to the digital space that we needed only a trigger event to kick off this mass physical decoupling from the workplace.

This is the modern compromise, for those who can get it: If you demand that my home is no sanctuary from work, then I demand that my home is where I work. In totality, this arrangement is perhaps suboptimal, but at least it’s an indicator that workers can push for a more logical arrangement. The Great Reclamation is evidence that the boundaries of work vs. home life are still being negotiated, and could be decided towards more healthy and productive ends going forward. In the meantime, though, in many a large institution, “healthy” isn’t for closers.

The King of On-ness

Adam Schefter’s rise, whatever its moral concessions, isn’t a purely sad story. He’s a driven guy, with a good reputation inside ESPN. On its face, you’d want an industrious person who gets along well with others to be the reporter who ends up making $9 million a year. The system worked, in that respect. The question is whether that system is working beyond whom it selects for. From the article, it’s hard to divine a strategy beyond the constant churn of beating press releases. Few fans probably care much about whether Schefter is happy doing what he does, but his mental state might be an indicator. He’s top dog in the top league at the company with a near monopoly on sports. Yet, from the article, he seems quite haunted by high-profile screwups that were motivated by his constant need to produce ahead of the information flow.

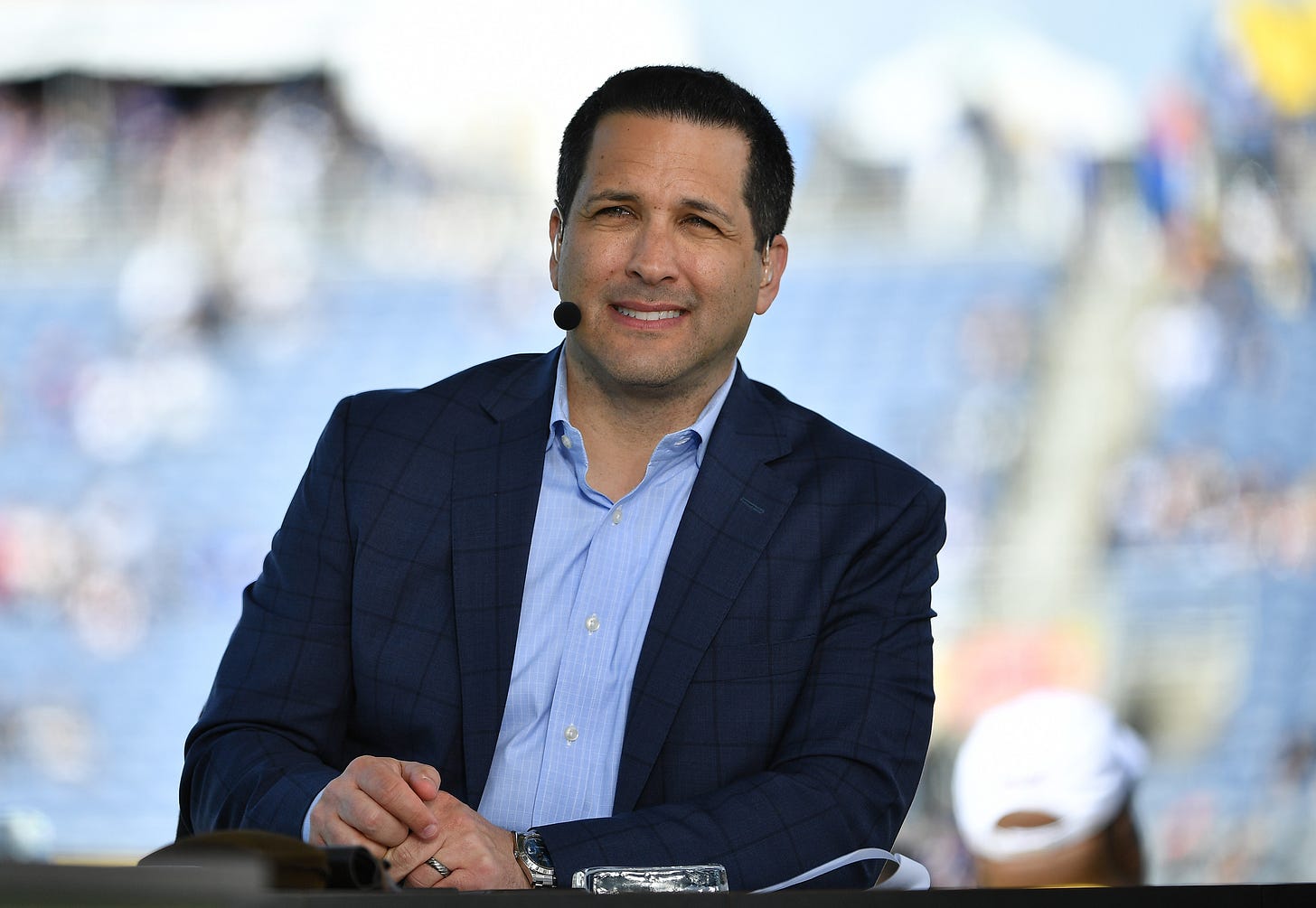

Many of those reading already know, but for those who don’t, Adam Schefter has become famous through his newsbreaking dominance on Twitter, combined with his enthusiastic omnipresence on ESPN airwaves. He’s the NFL version of Adrian Wojnarowski, except well-liked by his colleagues and good on TV.

How does he do it? Through many means and skills, but above all, it’s his work ethic. But I think it’s selling it short to call Schefter’s commitment “work ethic.” No, this is something else, and it’s thoroughly modern. Schefter’s extreme success is the result of endless vigilance. In any era, he’d be hardworking. But in this era, he’s always lurking. His free time just seems like a liminal space between being on and off the clock.

From Ben Strauss:

Chris Mortensen, another ESPN insider, called Schefter “the best to ever do what we do.” Mortensen set boundaries on his time, such as when Markman once called him on Christmas to do a live hit on ESPN. Mortensen said no; Schefter never does. “I’ve never set boundaries,” Schefter said. “That’s one of the reasons ESPN and I get along so well.”

Imagine giving yourself over so completely like this. I couldn’t do it but I respect such an act of radical commitment. It’s hard to argue against the basic results. Schefter is rich and famous. So how does he do it? Indefatigable on-ness.

Schefter said he doesn’t consider himself a talented writer or TV presenter; he is armed only with his work ethic and his ability to always be on. He tries to respond to every text message within seconds.

I’m reminded of what happened when Kevin Durant announced his joining the Warriors on July 4th, 2016, back when I was an ESPN reporter. In the days leading up, I’d been doing forgettable TV hits about the KD possibility outside Oracle Arena, according to a constantly shifting schedule that kept either scuttling or disallowing any plans in my life. The way TV works at ESPN is remarkably ad hoc, due to its constant state of live news reaction. A producer wants you for the 12 pm SportsCenter, but after you show up to the shoot in your suit at 11 am, you get word that it’ll actually be the 3 pm SportsCenter. But no, wait, it’s gonna be the 12 pm SportsCenter after all, and can you maybe stick around for the 6 pm SportsCenter? This is what it’s like, and I’m just describing, not complaining. It’s better than many jobs, especially if you like being seen, but it does mean living in a perpetual state of flux.

Obviously I had to work on the day of the actual KD signing, grilling national holiday be damned. So I wrote whatever I wrote, and made myself available for live shots out of the home office. But ESPN wanted more, bigger, better. There was a demand that I leave and hole up at the Oakland Marriott for hours if not days of more hits. They couldn’t say when it would end, only that it was beginning, at this very moment.

It was then that my wife said “no.” She’d had enough. I’d been on the road from preseason to Finals, covering the 73-win Warriors and their bid for history. That was a career windfall but it wasn’t the lifestyle she signed up for when we met. While she could usually tolerate the job’s omnipresent impact in our home, and how no plans could be made ahead of time during spring, a limit had been reached. No, you aren’t suddenly packing up again. No, you aren’t spending July 4th and beyond at the downtown Marriott, as opposed to in our house, where we theoretically live together. And so I declined, on her behalf, politely as I could. It did not go over well.

ESPN producers weren’t necessarily wrong to request what they wanted, even if I could bore you with a granular explanation about why TV work wasn’t my job, specifically. It’s all besides the point. If I wanted to rise in the company, I had to contribute when needed, and this was one of those times. Then again, all the other times can feel like one of those times, but that’s part of what separates those who can fetch a handsome living over there from those who can’t. It’s not like everyone can get paid well. Among the nonathletes, there’s got to be a differentiator, and one of the main ones is full commitment. To ascend, you must be without boundaries.

You see, doing TV at ESPN is interminably time-consuming, a neverending marathon of “hurry up and wait.” The system is such that you can’t just do a little bit of TV either. You’re either available all the time, or you’re off the list. Starve or explode. What I’m saying is, you have to really want it.

Adam Schefter really wants it. Whatever his mistakes as a reporter, he earns his success. It’s no accident that he rose to the top. He’s obsessively, maybe even myopically committed to the game, willing to go above and beyond the efforts of competitors. I question the tangible value of this whole “tweet out a trade first” enterprise, and believe it brings negative externalities to the Worldwide Leader, but can’t really deny that it rewards dedication.

Schefter’s rise is an inspiring tale from a certain vantage, a triumph of grit and focus. So why am I not inspired? Mostly because there’s grimness to victory:

Asked if he still had fun doing the job, Schefter said it has changed, and maybe he has, too. “Everything is heavier,” he said. “And so much faster. My wife tells me it’s stressful to eat with me because I eat so fast. Did I use to eat this fast? I don’t know.”

The article ends on the juice that keeps Schefter going:

Then he brightened, thinking of a moment from this year’s NFL draft. He was at his son’s graduation and supposed to be off, but the details of a huge trade came trickling in. “You’re ... getting the information in real time,” he said, his voice rising. “There’s a rush to that, and you feel it.”

If this is victory, then give me defeat.

Working Smarter

In 2011, James Andrew Miller and Tom Shales published a fascinating oral history of ESPN, titled Those Guys Have All the Fun. It wasn’t a book about a perfect company, but it was a book about a largely beloved one. It’s a massive tome, but you won’t see much discussion in it of how the job is “heavier,” or “faster.” The main complaint featured is that it sucks to live in Bristol, Connecticut. And yes, people worked hard back then, but they did so in such a way that their enthusiasm was contagious and charismatic.

While the Other Strauss article relays an argument for Schefter’s approach on the basis of granular TV ratings, it’s not like ESPN is more watched than it was when it started down this road of Twitter on the teevee. Indeed, it’s far less watched and people kind of hate the brand now. That dislike might be related to how the on-ness model erodes a connection to audiences in hard-to-quantify ways. For example, in order to consistently break news in some leagues, you have to do the bidding of agents, people whose perspectives aren’t in line with the those of sports fans. As top reporters speak to the fans, in public, they start to sound like how top agents speak to them in private. Sometimes, watching ESPN feels like viewing a snippet of a sci-fi movie where the alien parasite is speaking through its host. The ESPN reporter wants you to know that your team has failed Unhappy Star Player who’s bailing without any pretense of loyalty to said team. Star need more help. Respect star choice. Don’t feeling have. Such unlikable messaging just serves as an another example of how winning the present can repel fans. Submitting to on-ness can turn a lot of people off.

To be clear, I’m not against hard work or competition. Indeed, I want my son to deeply believe in the benefits of both. What I’m against is the modern condition of on-ness. I want systems that favor working over lurking. In the former you can have fun. In the latter, you’re a distracted mess, even at the millionaire level.

Nobody in particular is to blame for this issue of on-ness, which is probably the case for many of our pernicious problems. We can’t ask a ruler to change the incentives, or force tech corporations to destroy their communication innovations. We’re all just living in the aftermath of choices nobody made. Every company wanted to communicate faster, for fear of being boxed out by the next company. And so this all took on its own inertia, until the differentiator of assiduousness was replaced by the differentiator of on-ness. A guy like Schefter used to take pride in showing up early and leaving late. Now he takes pride in never leaving because he never has to, and, based on what his job wants, never should. And that’s the type of person many of you are competing against. So you’d better lurk and remove any boundaries when called into action, in theory.

The Schefters in our lives aren’t villains. They’re just trying to win, according to the rules. So I guess the question is, is this system what we want, overall? Perhaps in some industries, yes, and in other industries, no, but it’s not like the era of social media-enabled on-ness has correlated with some sort of productive utopia. It’s not like we’re constantly building the next version of the Golden Gate Bridge, and it’s not like the modern economy inspires much confidence. Lurking hard has correlated with some improvements, but the current conventional wisdom is that technological innovation has slowed down.

On the social level, our lack of boundaries has come with a lot of distractedness. I’m not saying it’s the cause of the big tech innovation slowdown, but it is so that major institutions now flit from hysteria to hysteria over current events, events that then bleed into the workplace conversation. Once an emotionally evocative news story reaches Current Thing status, it’s liable to needlessly envelope the Slack Channel discourse of countless corporations. How could it not? There’s no home life sanctuary, and people need to process their greatest obsessions somewhere. Next thing you know, your company is out beyond its remit, addressing issues that have nothing to do with the core mission. That is, if anyone can even remember the core mission in a corporation that’s perpetually reacting.

Boundaries are good, even if it’s true that Schefter thrived by eschewing them. Remove the boundaries and organizations can go a bit mad. Our ability talk to each other, all at once, constantly, was a thrilling development. Such a setup can, theoretically, make for a fun virtual sports bar or salon.

As a workplace, though? Far from a fun dynamic, and the results of modern hypervigilance aren’t so impressive. Faster, constantly, forever, might be good for options trading, but is less optimal for the generation and execution of ideas.

The good news is that almost everyone secretly hates this state of affairs, which means there’s at least a will to change it going forward, given the right opportunity. When I was interviewing at startups in my 20s, they’d try and woo prospective employees with kegs and table tennis setups. Perhaps the corporations of the future will offer recruits the promise of compartmentalization. Their reward might be not just the recruits themselves, but sane and sustainable productivity, towards tangible ends.

“He’s the NFL version of Adrian Wojnarowski, except well-liked by his colleagues and good on TV.” 🔥

I’ve been remote pre-pandemic and this struggle is an ongoing one. It’s easier if you don’t like your work - I do, and work is where I live, so the lines are constantly blurred no matter how many guardrails I put in place. It is especially difficult when, like many people in companies today, you work with people across time zones - there really is no time to naturally be “off”. We’re just getting started figuring this out

I’m in management (and a worker too) in the high-end client service business. Think investment banking, business consulting, big law firm, etc. Adam Shefter’s life is the way this business works, and it really grinds you down. We would love to see our people (and ourselves) be un-tethered, non-lurking from time to time. But here’s the thing: if you aren’t available when the client wants you, then you will be replaced. Period. There’s a pseudonymous guy who writes online as ‘The Epicurean Dealmaker’ who has written about this in the investment banking industry.

Ultimately, you have to operate that way to stay in the business or you have to leave. Because there is an army of Shefters out there willing to be on constantly and that’s who you’re competing with.

I appreciate this article a lot. Makes me think about the business and how it can change —- but I’m not seeing easy solutions (or really any solutions other than exit of all non-Shefters).